Michael Bresalier is a lecturer in the history of medicine at the University of Swansea. He is also a member of EPIC and will contribute a case study on epistemic injustice in tuberculosis vaccination programmes.

|

| Michael Bresalier |

Hi Michael! What is your main research interest?

My research interest has been with the production, legitimisation, circulation, and consequences of biomedical knowledge of human and animal health and disease. Much of my work has been on infectious and zoonotic diseases (infections that move between human and non-human animals).

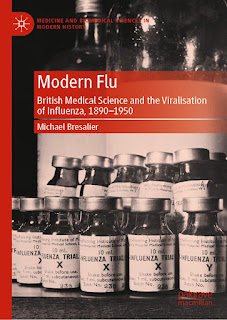

My new book, Modern Flu (Palgrave 2023), traces the long process by which influenza was framed as a viral disease and how new virological ways of knowing influenza reshaped clinical, public health and popular approaches to the disease.

A key concern of mine is with how disease categories vary and change, and how they are negotiated and incorporated into medical practices and experiences (broadly construed). I am especially interested with how agreement is formed in medicine at various levels, whose ideas and interests are included or excluded in the process, how medical knowledge is or is not shared, and the ways agreed disease concepts or definitions affect diagnoses, treatment, and access to healthcare resources.

Why do you think it is important to study epistemic injustice in healthcare?

Although people working on the history, anthropology or sociology of medicine and health have used different terms and frameworks, forms of epistemic injustice have been a central concern for some time. Among other things, what such research has shown is that differentials in patients’ and sufferers' testimonies or the knowledge they possess to negotiate health or illness are socially determined and have shaped healthcare systems and health outcomes.

But I think epistemic injustice is an important framework for gaining critical new insight into how power relations operate in healthcare and, most importantly to me, as way to think about what justice in healthcare might look like and what forms it might take. This kind of normative move is not something historians usually make. Collaborating on this project is a great opportunity to reflect on how historical perspectives can help address epistemic injustice and make healthcare more equitable.

What are you working on right now?

I have been working on a couple of different projects that tie into EPIC. One is a study of ‘gift’ economies in global health and medicine, with particular focus on policy and practical arrangements that have developed to facilitate ‘sharing’ vaccines between high-, middle- and low-income countries. I am interested in how different actors and organisations conceive of gift-giving as fundamental (or not) to addressing global health inequalities, including epistemic inequalities (i.e., the sharing and exchange of knowledge in making or delivering essential vaccines).

A related project examines the implementation and experience of ‘selective' tuberculosis vaccination programmes in the UK (and elsewhere), that have targeted ethnic minority communities from or connected with countries that have a high incidence of tuberculosis. The project will integrate archival research on TB vaccine policies and programmes with oral histories/ethnographic studies of medical practitioners, TB service providers, parents and children, among others, to examine how selective vaccination has been framed, understood and experienced by different groups.

A key aim is to highlight how uncertainties about TB vaccination have been negotiated as way to better understand vaccine hesitancy, while another is to empirically test if and how epistemic injustice manifested in vaccination policies or programmes. This will be the focus of my EPIC case study, 'Negotiating Immunisation: Epistemic (in)justice in tuberculosis vaccination programmes’.

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated.