Laura was brought to the emergency department (ED) by ambulance after a pharmaceutical overdose. Earlier in the assessment, she said she visited her General Practitioner earlier in the day seeking mental health support but she didn't feel she got the support she needed. She reported that she later took a pharmaceutical overdose because she felt very suicidal. The practitioner Laura talks to in the ED recharacterizes Laura’s experience of suicidal ideation as brief and her act as impulsive.

"From a philosophical perspective, applying the concept of epistemic injustice to the clinical encounter enables us to conceptualize the attitude of an epistemically privileged party not as a lack of respect or a failure of empathy (which would not be specific enough) but as an act of injustice toward the party who is epistemically subordinate. The injustice amounts to assigning reduced credibility to a patient’s reports, effectively preventing the perspective of the patient from contributing to shared knowledge and decision making. As epistemic injustice concerns knowledge first and foremost, this does not simply tell us that dismissing a person’s perspective due to prejudice is morally objectionable. Rather, it is problematic from an epistemic point of view because the opportunity to gather knowledge that would benefit both parties and society at large is missed."

|

| Clara Bergen |

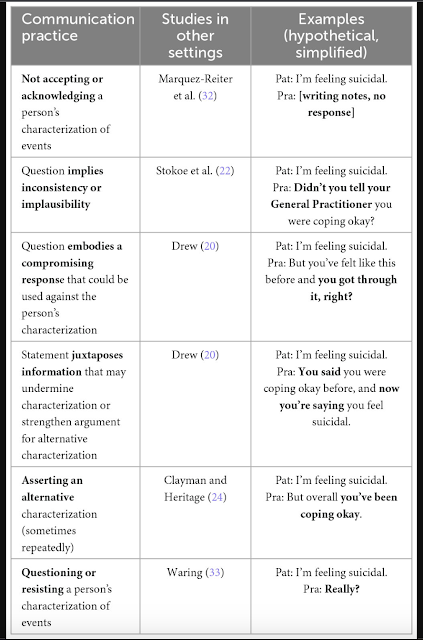

In this table from the paper, we can see that several studies have already gathered evidence of this practice of implying implausibility or undermining the patient's report of their experiences, and that the practice can take several forms:

In the case I started with, one of the five cases examined in the paper, young person Laura's reported intention to kill herself is challenged on numerous occasions, via different strategies:

- asking questions that anticipate a compromising response ("And I hear you called the ambulance straight away?");

- asking questions that imply implausibility or inconsistency ("So when you called 111 what did you expect them to do?");

- juxtaposing contrasting information ("You called them so that they could get you help");

- implying information that provides evidence of an alternative characterisation ("So would you say that you took the tablets at the spur of the moment?").

As a result of the encounter, the practitioner concludes that Laura took the tables impulsively and suggests that, if Laura feels suicidal again, she should get support from people she knows or call the Samaritans. The involvement of the rapid response team is deemed unnecessary, and Laura is not referred to mental health services.

|

| Rose McCabe |

Future research should explore to what extent recharacterization could be minimized through further communication training or unconscious bias training, and to what extent a long-term solution may lie in increasing accessibility of mental health services for people who self-harm and experience suicidal ideation.

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated.