noun, epis·te·mol·o·gy i-ˌpi-stə-ˈmä-lə-jē

the study or a theory of the nature and grounds of knowledge especially with reference to its limits and validity

It struck me that the diversity of our group was evidence that expertise in Adverse Childhood Experiences and developmental trauma cannot be held by any specialty. Nobody can claim epistemic dominance. Like the blind men feeling an elephant and each being certain that the whole creature resembles the part they are feeling, in matters of trauma nobody can claim to be able to see the whole picture. Modern medicine is structured with specialists at the top and generalists (like GPs) at the bottom.

The Telegraph newspaper has had a series of headlines recently pointing out that GPs don’t know enough about cancer or antidepressants or anything else. According to The Telegraph if people are sick, they ought to a specialist. These are easy accusations to make and have been news headlines for my entire career and will continue until journalists understand and value the fact that generalist knowledge about the ways different illness interact is not the same as the accumulation of number of different specialisms. There were two GPs at the LAH dinner and drinks, evidence perhaps that GPs more than any other specialty see the ways that biography and biology are constantly affecting each other leading to familiar pattens of physical, psychological, and social disruption. Nevertheless, our medical perspective only captures part of the picture which is why our group includes people working in criminal justice, racial justice, education, community activism, parenting support, and more. We depend on one another to see the whole picture.

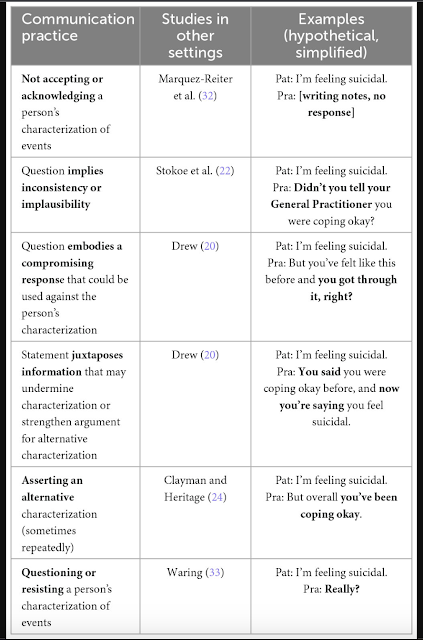

A few days after the dinner, I attended an interdisciplinary workshop about trauma with philosopher Havi Carel and a range of speakers including philosophers, literary scholars, educators, and a music therapist. Once again, none of us could claim epistemic dominance. Professor Havi Carel is perhaps best known for her work on Epistemic justice in healthcare. Epistemic injustice in healthcare happens when a professional assumes that because of certain characteristics their patient is an unreliable narrator and interpreter of their own experiences. Consequently they fail to listen to or take seriously what their patient has to say. The only story that counts is the medical history and the only interpretation that matters is the diagnostic formulation. Patients experience not being seen or heard, i.e. invalidation.

People who are suffering the consequences of trauma, living with what I describe as the trauma world of hypervigilance, shut-down, toxic shame, dissociation and harmful coping strategies, are especially likely to have characteristics that professionals assume render them unreliable witnesses. These include being a child or female or trans, being black or other ethnic minority, being neuro-divergent or having a mental illness, having any kind of physical or mental disability, having an addiction past or present, being homeless, having low levels of literacy or educational attainment and so on. Intersectionality matters, so a Black woman with a mental illness and an addiction is subject to multiple assumptions and is especially vulnerable to Epistemic Injustice. One of many valid definitions of trauma that I’ve heard from researchers including Bessel van de Kolk and Jacob Ham as well as survivors is,

“Trauma is not being seen or heard.”Trauma happens under conditions of overwhelming stress where those affected are unable to talk about what’s happening because it is too dangerous or there is nobody who will listen. They learn to bottle it up and in so doing, increase the risk of the kinds of inflammatory and autoimmune disease that are hugely over-represented in people with traumatic life histories. A healthcare professional represents someone with power who may cause the patient to re-experience feelings of powerlessness, but also has the potential to provide a safe environment and attuned presence. If they feel safe enough, patients may want to talk about what has happened to them. If we refuse to listen or don’t listen carefully enough, then they may experience the traumatic invalidation that they have suffered before, and the potential harm is enormous. Patients with trauma are at greater risk of Epistemic Injustice and suffer greater harm from it.

My own Achilles heel as a doctor is explaining too much. I recently discovered a quote from Donald Winnacott, a child psychotherapist and paediatrician who worked near my practice over 50 years ago and it was reassuring to know that we have at least this in common:

“It appals me to think how much deep change I have prevented or delayed in patients in a certain classification category by my personal need to interpret. If only we can wait, the patient arrives at understanding creatively and with immense joy, and now I enjoy this joy more than I used to enjoy the sense of having been clever. I think I interpret mainly to let the patient know the limits of my understanding. The principle is that it is the patient and only the patient who has the answers. We may or may not enable him or her to encompass what is known or become aware of it with acceptance.” Playing and RealityIn my teaching about trauma, I use a quote from Leslie Jamieson, The Empathy Exams:

“Empathy is asking the questions whose answers need listening to.”I hope to persuade the doctors and students that I teach, as well as constantly reminding myself that you can demonstrate your expertise by the questions you ask. In so doing we can enable patients to tell their stories and come up with interpretations that help them make sense of their experiences. It’s important to remember that figuring why you are like you are doesn’t necessarily make things better, and may even make things worse, but it is a necessary part of a healing process. Making sense of painful lives through stories is not a radical departure from clinical medicine, but an essential and inseparable part of it. Stories are how medical knowledge is transmitted and ‘how doctors think’ even if we’re unaware of it.

In summary, understanding epistemic (in)justice is essential for trauma-informed care because patients affected by trauma are more likely to not be listened to or taken seriously and are more likely to be harmed by invalidation. Because no specialty within medicine can claim epistemic dominance, they experience what Psychoanalyst Michael Balint described as the ‘collusion of anonymity,’ where “the patient is passed from one specialist to another with nobody taking responsibility for the whole person.”

The answer for me lies in creating a safe environment and continuity of care with well cared-for and respected generalist professionals who can truly listen.

Thanks to Flo, who has been helping me teach this and has inspired me to try to figure this out.

Jonathon is especially interested in the intractable problems that characterise 'deep end' general practice like complex-trauma, chronic pain and the intersections between biography and biology.