During #PhiloFortnight2025 the British Philosophical Association launched a campaign to raise awareness of the role of philosophy in our lives. As part of this initiative, EPIC at Birmingham organised a webinar to launch the recently published open-access book, Epistemic Justice in Mental Healthcare (Palgrave 2025).

|

| Poster of the event |

The panelists (all partners of project EPIC) presented their research and then engaged in discussion about the importance of the notion of epistemic injustice and the strategies we should adopt to reduce the harms that come from it.

In this post, I want to share our conversation about what we might call "the added value of epistemic injustice": when we analyse patient-doctor relationships and clinical interactions more broadly, we tend to use a variety of concepts, including person-centred care, feeling understood, dignity, trust, social health, good living, and agency.

What does the appeal to epistemic injustice add to these analyses? Aren't the concepts we have used so far, those that preceded the application of the notion of epistemic injustice to the heathcare context, sufficient? Each of the panelists gave an insightful reply to this question.

|

| A slide from Michael's presentation on feeling understood |

Michael Larkin described a case he encountered in a paper on consent where a young man hit one of the doctors. When he was asked why, he said that he did so because he was angry. But then in interactions with other doctors, this idea that anger was what caused the young man to act was challenged and reinterpreted: one doctor said that the young man acted that way because he was delusional.

Another doctor said that the young man acted that way because he had schizophrenia. And the young person did not recognise these as reasons why he hit the doctor, repeating that yes, maybe he was delusional and he had schizophrenia, but he acted that way because he was angry. Michael remarked that the notion of epistemic injustice would have been very useful in that context, due to its precision, because it precisely identifies a failure to recognise knowledge.

|

| A slide from Rose's presentation about clinical communication |

Rose McCabe remarked that the idea of "injustice" is also very important in the notion of epistemic injustice and goes beyond what we may convey when we talk about trust. Although people who use services know when this happens, when healthcare professionals dismiss or reinterpret what they have to say in a way that misrepresents them, they don't always have the right language to report it or to refer to it.

Having a way to reflect on communication and the respective epistemic stances in clinical interactions is valuable. Also, research on epistemic injustice is welcome because relationships and communication are crucial to the experience of services by people who seek help, but have not always been the focus of research. The epistemic injustice literature has zoomed in on those issues.

|

| A slide from Luigi's presentation on dignity |

Luigi Grassi observed how rejecting a person's explanation for their own behaviour because they are delusional is not the only situation in which epistemic injustice happens: when people talk about their symptoms, even when they are not diagnosed with a serious mental illness, doctors often tell them that it is all in their head, do not believe them, and even suggest that what they are reporting is not possible.

Epistemic injustice is an important new perspective that is central to research and training and should be made into a tool -- just like there is a dignity inventory there could be an epistemic injustice inventory.

|

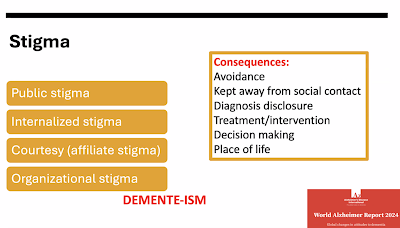

| A slide from Rabih's presentation on stigma and its consequences |

Rabih Chattat argued that talking about epistemic injustice is not the same as talking about stigma because the notion of justice brings to the fore that there are rights that are being violated, such as the right to self-determination, and this is evident in the treatment of older people with dementia.

To this, Rose added that epistemic injustice also enable us to see important connections between what happens in healthcare (where a doctor may dismiss the subjective experience of a patient) and what happens in other contexts where there is a power imbalance (for instance, where a teacher dismisses the perspective of a student).

|

| A slide from Elisabetta's presentation on bias in diagnosis |

Elisabetta Lalumera highlighted another aspect of epistemic injustice that is very distinctive. When we treat an expert as a non-expert, we act unwisely. When we are committing epistemic injustice, it is not just that we are not being nice to the person who is sharing their knowledge, but we are also throwing out valuable information because of a prejudice. It is a mistake of judgement that harms us as well as the person whose knowledge we dismiss.

If you are intrigued by this discussion and want to watch the whole webinar, it is available here:

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated.