This week we announce the publication of an edited collection which is entirely open access: Epistemic Justice in Mental Healthcare: Recognising agency and promoting virtues across the lifespan (Palgrave 2024), edited by myself, Lisa Bortolotti. The book is an output of project EPIC, featuring eight new chapters exploring epistemic justice in mental health.

|

Epistemic Justice in Mental Healthcare

|

In the Preface (downloadable here), Matthew Broome and I frame the discussion as a way to affirm the role of the mental health patient as a person, an agent, and a collaborator. When we are mental health patients, we are persons because we are more than our health or our diagnosis, we have needs and interests that matter and that affect the way in which our health impacts our lives.

We are also agents, because despite the vulnerabilities of our status as patients, we have a perspective that matters and the capacity to contribute to positive change. Crucially to the success of clinical encounters, we are partners in the project of addressing our health issues. We can collaborate with healthcare professionals by sharing our experiences and participating in decision making.

Chapter 1, Being understood: epistemic injustice towards young people seeking support for their mental health, is authored by Michael Larkin with members of the Agency Projects team including lived experience researchers from McPin. It addresses some of the factors that make clinical interactions unsuccessful, offering some suggestions for improving clinical communication. The focus is on ensuring that young people are understood and supported at times of crisis, that they are not blamed for the difficulties they face, and that they are not reduced to a diagnostic label.

Chapter 2, Challenging stereotypes about young people who hear voices, is authored by myself, Lisa Bortolotti, Kathleen Murphy-Hollis, Fiona Malpass, and young people from the Voice Collective. It highlights three stereotypes associated with voice hearing that have harmful consequences for young people's relationships and opportunities to thrive, in the family, the school, and the clinic. These are incompetence, dangerousness, and diversity leading to exclusion. The chapter illustrates the impact of these stereotypes based on the young people's experiences, and encourages further empirical research in this area.

Chapter 3, Reacting to demoralization and investigating the experience of dignity in psychosis: reflections from an acute psychiatric ward, authored by a team led by Martino Belvederi Murri, addresses the unique challenges to epistemic justice that emerge in an acute ward, where coercion may be used. The use of coercion may engender situations that are detrimental for individual dignity and morale. One such effect is demoralization, which may increase the risk of suicide. The chapter provides an overview of the work on these topics and offers some suggestions for strategies that might improve the experience of psychiatric inpatient care.

Chapter 4, Not all diagnosis are created equal: Comparing depression and borderline personality disorder diagnoses through the lens of epistemic injustice, authored by Jay Watts, examines four aspects of epistemic injustice: objectification, moral agency, trivialization, and narrative agency. It compares personality disorder and depression, arguably the least and most popular diagnoses with patients in psychiatry. The analysis emphasises the importance of epistemic injustice as a tool in critically evaluating the usefulness of specific psychiatric diagnoses, encouraging a shift in clinical training to embrace reflective practices and restructure power dynamics in clinical encounters.

Chapter 5, Resisting perceptions of patient untrustworthiness, authored by Eleanor Palafox-Harris, argues that a beneficial therapeutic relationship between patient and clinician requires mutual trust. In order to effectively treat someone, a clinician has to trust the patient’s reports of their symptoms but many psychiatric diagnoses are stereotypically associated with traits that indicate untrustworthiness (such as irrationality). In this chapter Palafox-Harris illustrates how psychiatric labels can signal stereotypes of untrustworthiness, reducing patients' perceived epistemic credibility.

Chapter 6, Preserving dignity and epistemic justice in palliative care for patients with serious mental health problems, with Luigi Grassi as lead author, considers the challenges faced by people with serious mental disorders who are at the end of life and promotes a person-centred approach, which can increase the sense of personal dignity and epistemic justice. Dignity Therapy can be applied in palliative care settings, offering people an opportunity to reflect upon crucial existential and relational issues and prepare their legacy.

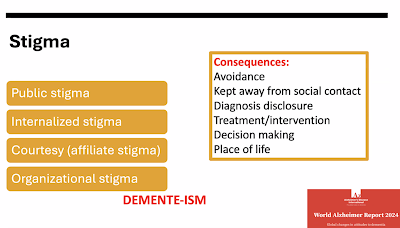

Chapter 7, Promoting good living and social health in dementia, with Rabih Chattat as lead author, explores the notion of good living in the case of dementia and highlights the role of social health in preserving wellbeing. Discrimination impacts people with dementia in diagnosis disclosure, advance care planning, and decision making. The chapter critically examines the labelling of the behaviour of people with dementia as problematic and pathological even when it is a reaction to difficulties in communication.

Chapter 8, Ameliorating epistemic injustice with digital health technologies, authored by Elisabetta Lalumera, discusses the potential of digital phenotyping for ameliorating epistemic injustice in mental health. There is a concern that the evidence digital health technologies gather may overshadow individual experiences but, through a fictional case study, Lalumera portrays digital phenotyping as way to support shared decision-making.

The book aims to help understand how the demands of epistemic justice relate to and complement recent research on agency in youth mental health, person-centred care, dignity therapy, stigmatising diagnoses, good living, social health, and access to digital technologies. As illustrated in the figure below, people seeking help should preserve crucial roles as agents and collaborators with valuable perspectives, multiple interests and needs, the capacity to contribute to positive change, and the capacity for shared decision making.

|

| The mental health patient as an agent |

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)